show selection |

|

ometimes you have to spend a little time in the trenches to fully understand what works and what doesn't. When Mara Weber started working in the marketing department at Phoenix-based Honeywell Process Solutions (HPS) - a supplier of automation control processes for several industries including the energy industry - she was responsible for attending the occasional trade show as a member of the HPS team. From her vantage point as a booth staffer, Weber realized that all was not well with HPS' trade show program. ometimes you have to spend a little time in the trenches to fully understand what works and what doesn't. When Mara Weber started working in the marketing department at Phoenix-based Honeywell Process Solutions (HPS) - a supplier of automation control processes for several industries including the energy industry - she was responsible for attending the occasional trade show as a member of the HPS team. From her vantage point as a booth staffer, Weber realized that all was not well with HPS' trade show program.

|

| ALL-STAR AWARD |

Mara Weber, manager of trade shows and events for Honeywell Process Solutions and directorof global Honeywell Users Group events, has 18 years of experience as a marketing professional. She has implemented strategies for a variety of disciplines, including trade show and event management, communications, and promotions. Mara Weber, manager of trade shows and events for Honeywell Process Solutions and directorof global Honeywell Users Group events, has 18 years of experience as a marketing professional. She has implemented strategies for a variety of disciplines, including trade show and event management, communications, and promotions.

|

|

To Weber, it seemed HPS had no consistent message, and the company seemed to send big booths to big shows regardless of past performance or attendee profiles. Add to that an obvious lack of booth training and no desire to promote its trade show presence before each show, and Weber felt she was looking at a potential economic engine for the company that, unfortunately, had been left idling.

So when the exhibit-marketing position opened up, Weber stepped in. But a dearth of information on the program's performance meant that Weber first needed to find the data to back up her actions - and she had to start from scratch.

The Way It Was

When Weber came on board in 2000, as a marketing staffer who helped primarily with HPS events such as road shows, roundtables, and HPS' user seminars, she was puzzled by the trade show program. "I really didn't feel there was a lot of strategy involved in decision making," Weber says. What's more, she identified a lot of wasteful and ineffective practices.

She noticed that HPS' exhibits were often staffed by chatty employees who showed up late and ignored attendees. Furthermore, the company seemed to constantly reinvent its exhibit-marketing message, creating new signage and booth literature, and purchasing new booth components or entirely new custom booths for new shows in new industries. This strategy was hardly a cost-effective - or efficient - way of doing business. But the waste went deeper than just signage and exhibit structures.

Weber found that the company's rationale for attending shows was often little more than "because we always have," without regard for changing attendee demographics or evolving exhibit-marketing goals.

HPS also signed up for booth space without considering the program's objectives based on attendee profiles or ROI, and it rarely tracked leads. The leads that HPS did gather at shows were given to sales staff but there was no system in place for tracking them further. This made it impossible to determine whether or not any actual transactions resulted from HPS' presence at any of the shows it attended.

And Weber's predecessor seemed averse to pre-show promotions, actively engaging attendees, or any kind of measurement. As a result, HPS' sales strategy looked like an exhibit-marketing program from decades past, mired in the old-school mantra that "If we exhibit, the sales will come."

Consequently, HPS management viewed trade shows as a distasteful necessity rather than a tool that could actually build business. Weber - first from her view in the marketing department, then from her strategic overlook as the program's manager - saw trade shows as an untapped source of sales, a value to HPS as part of an overall face-to-face marketing program. And she was determined to make sure her company saw that value.

Mara in Charge

When Weber took over the program in 2004, she planned to turn HPS into a marketing machine. Luckily, her promotion coincided with a change in leadership at HPS, and the new management felt Weber was onto something. Management's decree: Make sure we're getting our money's worth from the trade show program.

Weber knew she wouldn't be able to wave a magic wand and fix her program overnight. Most booth-space contracts for 2005 had already been signed, so making changes to her trade show calendar was out of the question. And even if she could make major changes, Weber wanted to make them based on cold, hard facts.

Despite the fixed calendar, Weber decided to start off with some basic booth-staff training - something missing from the previous regime. She also started promoting HPS' presence at upcoming shows, beginning with e-marketing campaigns to drive traffic to the booth.

In addition to these minor tweaks, Weber knew she needed some help if real change were to come. She needed information about the shows HPS attended. "We needed to know who the audience was at each show to help us identify whether or not we were spending wisely," Weber says.

Weber turned to her exhibit house, Milwaukee-based Derse Inc., for help. Since HPS had no survey or audit of its own, Derse considered factors such as total attendance, professional attendance, target audience, the number of exhibit-hall hours for each of the key shows on HPS' calendar, and competitive-opportunity analysis - a look at how HPS' competitors approach each show to see how the competition is serving attendees. Derse then compared the show data it compiled to a detailed target-audience profile Weber supplied that identified the kinds of attendees HPS wanted to target. Through that analysis, Derse determined which shows were the right fit for HPS, which shows warranted a smaller HPS presence, and which shows needed to be dropped.

Derse also looked at past years' attendance for each show and determined how many attendees fit Weber's profile. Using that information, Derse made recommendations on how much HPS should invest in each show to reach targeted attendees, the optimum booth size based on the show's attendance and the percentage that fit HPS' attendee profile, and the number of booth staffers the company would need to handle the expected attendee load at each show. Derse even looked at the sponsorship options available and made suggestions based on the information it had gathered.

Data in hand, Weber's next step was to approach product managers at HPS and ask them to identify desired target markets and the objectives for reaching those markets. Essentially, Weber asked each product manager to justify his or her department's reasons for attending each show, while also ranking shows based on how valuable they had been in the past. Weber then established a rating system, based on the product managers' wish lists and the information supplied from Derse. This allowed her to evaluate each show on her annual calendar and determine which ones HPS should attend.

|

|

|

|

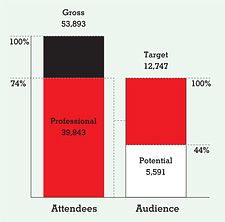

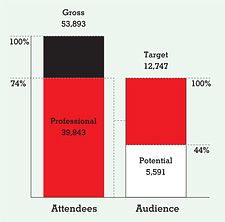

CRUNCHING THE NUMBERS

Mara Weber used data collected by her exhibit house, Derse Inc., to help analyze the shows on her company's annual calendar. The following calculations, based on data from the 2006 Global Petroleum Show (GPS), illustrate how Derse spliced and diced attendee information to identify each show's Potential Audience and make recommendations regarding the number of staffers and square feet of booth space each show warranted.

|

STEP 1. After a detailed analysis of each show's demographic and/or independent audit data, Derse identified HPS' Potential Audience, which is the number of attendees (based on everything from gross attendance to Audience Interest Factor) the company could expect to visit its booth during the show. In this example, Derse used independent audit data from BPA Worldwide and Exhibit Surveys Inc. to estimate that 5,591 of the show's gross attendance of nearly 54,000 people comprised HPS' potential audience. |

|

|

|

|

Change is Good

Based on internal HPS data and Derse input, Weber made changes to the trade show program for 2006, reducing the calendar from the 35 shows attended in 2004 and 2005, to just 24 shows in 2006.

Referring again to the data she obtained from Derse, Weber then analyzed each show that remained on her calendar to determine an appropriate investment and to identify more efficient exhibiting methods.

For example, Honeywell historically had several divisions represented in various small booths scattered across the show floor at the Offshore Technology Conference (OTC), a giant show in the oil and gas industry. While the show had grown in recent years, Derse's research indicated that while total-show attendance was up, the percentage of those attendees who fell into HPS' target audience had actually declined. So HPS partnered with other Honeywell groups that were planning to exhibit at OTC and shared one large corporate booth, a move that translated into decreased costs for each individual division.

Another example of how her data was used to increase her program's efficiency was the Exfor conference, a show to which HPS traditionally brought a 50-by-50-foot exhibit. However, Derse's research indicated HPS only needed a 10-by-20-foot exhibit space to reach its desired target audience at this conference, mainly because a large percentage of Exfor attendees fell outside of Weber's target-audience profile.

In addition to cutting some shows and decreasing her investment at other shows, Weber found even more ways to increase her program's efficiency. For example, she purchased interchangeable booth components that can be mixed and matched for use at various shows, customer events, and other venues, putting an end to HPS' wasteful practice of purchasing new properties for each one-off event that came down the pike.

She also saved money by printing general booth signage and collateral, rather than printing new show-specific materials for each event.

Reports of Her Own

With her new show calendar in place for 2006, Weber began installing a measurement and reporting system throughout HPS to help her quantify her program's success and establish a benchmark for future measurement.

Her system was designed to count and qualify leads, track sales back to trade shows, and report ROI for each event. Implementing the process took time (especially for training staffers to follow leads through HPS' lengthy sales cycle) and money (lead-retrieval systems, more in-depth pre-show marketing efforts, etc.), but Weber is now seeing the payoff. Though HPS' numbers are still just beginning to roll in, early returns show a 71-percent increase in leads generated from late 2006 through early 2007. That data not only represents program-wide improvements, it also represents a baseline for her to use in an ongoing attempt to gauge the effectiveness of her program and the shows she chooses to attend.

In 2007, Weber again turned to Derse to help her develop and report goals. As a result of that partnership, Weber now develops a strategic show brief for every show HPS attends. She distributes the brief, which lists the company's measurable goals, to booth staffers so they are always aware of what the company hopes to achieve at each show. Then, Weber circulates a quarterly report, reminding all internal stakeholders of the original goals for each show, and comparing them to the results her program achieved.

With systems now in place to set goals and report results for each show, Weber has made results part of the equation for every trade show and event decision HPS makes. To Weber, though, the biggest change is how management perceives the trade show and events program.

"In the old days, our executives didn't spend a lot of time looking at the program," Weber says. "Today they do. Now they are asking questions about things like our ROI or attendees that they wouldn't have known to ask about in the past." In other words, as one All-Star Awards judge said, "Mara did one of the most difficult things to do in trade show marketing: Through her data-based approach, she changed the perception of the function of a trade show."

From her humble beginnings as an HPS booth staffer, Weber has risen in her company's ranks and elevated the profile of the company's trade show program. It just goes to show, the view from the trenches can sometimes be the very best seat in the house. e

|

|

|

|

|

|

ometimes you have to spend a little time in the trenches to fully understand what works and what doesn't. When Mara Weber started working in the marketing department at Phoenix-based Honeywell Process Solutions (HPS) - a supplier of automation control processes for several industries including the energy industry - she was responsible for attending the occasional trade show as a member of the HPS team. From her vantage point as a booth staffer, Weber realized that all was not well with HPS' trade show program.

ometimes you have to spend a little time in the trenches to fully understand what works and what doesn't. When Mara Weber started working in the marketing department at Phoenix-based Honeywell Process Solutions (HPS) - a supplier of automation control processes for several industries including the energy industry - she was responsible for attending the occasional trade show as a member of the HPS team. From her vantage point as a booth staffer, Weber realized that all was not well with HPS' trade show program.