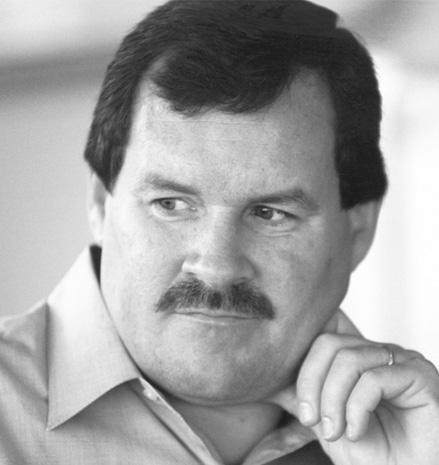

EXHIBITOR LEGENDS AWARD WINNER

After Jack McEntee attended Philadelphia's Temple University on a basketball scholarship, the one-time communications major switched to history, becoming a high school teacher after graduating in 1968. Frustrated by the lack of opportunity, McEntee went to work for Convention Service Inc. in Philadelphia, and four years later in 1979 launched I&D Inc., among the very first exhibitor-appointed contractors (EAC). Stymied by the stranglehold Freeman Cos. had on labor in show halls, McEntee sued, and started a revolution on the show floor, opening it up to other EACs.

|

ome names become so popular that they evolve into generic terms for an entire industry. Think of Xerox for photocopies, Kleenex for tissues — and I&D for installation and dismantle. While those products and services are as different as rhubarb and rubies, the story behind each of those catch-all terms is almost always the tale of someone with a work ethic that could be measured in megatons of energy, and who filled a void big enough to hide aircraft carriers — all of which describes Jack McEntee to a T.

Born with a gift for inspiring, McEntee started his career coaching basketball and teaching history at a Gloucester City, NJ, parochial high school. Discovering that teaching was immensely satisfying but deeply impoverishing, he joined the exhibition industry in 1974 with Convention Service Inc. in Philadelphia. After five years of learning the ropes, McEntee took his fate into his hands like a bounce pass from a teammate. Together with partners Tony Amodeo and Pat Alacqua, he founded I&D Inc., which became one of the industry's first independent labor contractors, or exhibitor-appointed contractors (EAC), allowing exhibitors to bypass the general contractors (GCs), aka show-appointed contractors.

After being shut out of the 1983 Offshore Technology Conference (OTC) held in Houston, McEntee embarked on a mission-impossible endeavor that made Don Quixote look like a hardnosed realist. Instead of tilting at windmills, however, McEntee sued Freeman Cos., one of the well-known GCs, to break the Dallas-based company's grip on parsing out labor to exhibitors in the show halls.

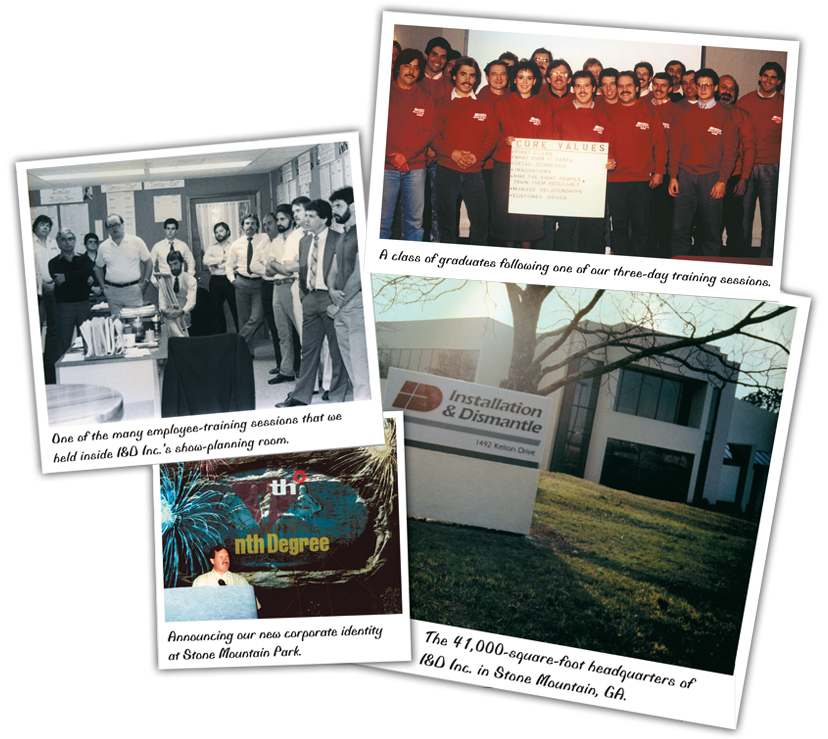

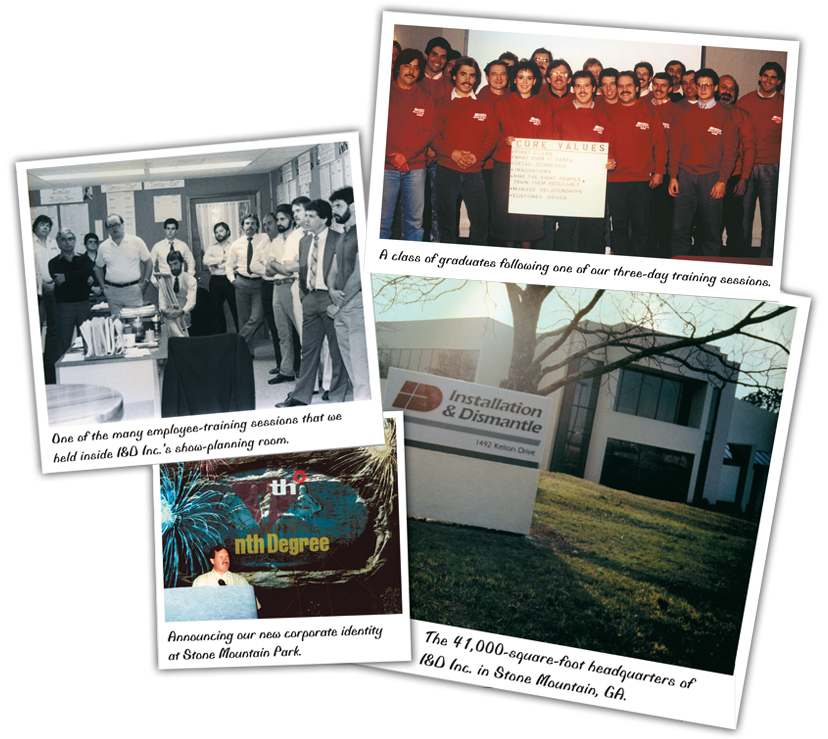

McEntee fought Freeman to a standstill — only to emerge victorious when trade show organizers decided they would rather spend their time producing shows than defending lawsuits. That triumph, in fact if not in law, propelled the Atlanta-headquartered I&D to become the largest independent contracting company in the nation, with offices in 15 cities. Later, in the 1990s, McEntee morphed I&D into the full-service event-management company, Nth Degree Inc.

Despite a jump to the exhibition industry, McEntee never wavered from his first calling as a teacher. McEntee trained and taught hundreds of employees exhibiting expertise and life lessons, nearly two dozen of whom later launched their own I&D businesses.

For his work in pioneering the rise of the EAC, the self-described "little guy" was honored at EXHIBITORLIVE last month with the EXHIBITOR Legends lifetime achievement award.

EXHIBITOR magazine: What made you enter the exhibiting industry?

Jack McEntee: It was the fastest way out of poverty. I was about 25 years old, coaching basketball and teaching at a Catholic high school in Philadelphia. But teaching in a Catholic school was about the same as taking a vow of poverty, and I was getting tired of being poor. That's when I applied for a job with Convention Service Inc.

EM: What did you do in your role at Convention Service?

JM: Mainly, I answered the phone a lot. The owners, Danny Molinaro and Steve Cahill, taught me everything. I learned the value of making sure customers know you sweat the small stuff on their behalf. Over time, I began introducing myself to these exhibit companies, my unofficial role got larger, and pretty soon I was generating a good share of the company's business. I was proud of myself, but I also knew that if I stayed there, I was always going to be just the guy who answered the phones. So in 1979, after five years at Convention Service, I realized that I needed to strike out on my own.

EM:

EM: What made you believe that you would be successful?

JM: In my five years with Convention Service, I had seen a growing need for something no one was addressing: Half a dozen GCs controlled everything at a trade show. It was a huge monopoly, and they changed the rules often and arbitrarily about what exhibitors could and could not do on the show floor. On top of that, they charged exhibitors heavily for the privilege. It was common for these GCs to send exhibitors maybe half of the laborers they were promised — and there was nothing the exhibitor could do about it. But I thought, what if there was an exhibitor-appointed company who contracted with labor unions for help, then offered more competitive pricing and more efficiency? The GCs didn't realize it then, but they were setting us up to succeed.

EM: So how were you inspired to name the company I&D?

JM: I wish I could claim I was the genius behind it, but I can't. Over the years I had become a good friend of Bob Baciocci, who founded Scope Exhibits Inc. in San Francisco. I had a bunch of names I ran by him — they were so forgettable I've forgotten them — and Bob listened to my ideas one by one. "Why don't you just call it 'I&D?'" he suggested. "It's what you do. If you call yourself that, you'll stand apart from everyone else." We never understood at the time how significant the name would become. I owe Bob big for that.

EM: How did you sell customers on the idea of an EAC?

JM: In the early '80s, the GCs handled everything on the show floor. When exhibitors wanted to get labor, they marched to the service desk and waited in a long line to get union people assigned to them. On the second day, though, they would get an entirely different group of workers, who of course were unfamiliar with their exhibits. The exhibitors despised that. We realized that if we could provide at least one "lead man" who would be consistent on the install and the dismantle, we would create a comfort zone for our customers. Needless to say, that idea — which some started calling "Same man up and same man down" — became a big hit. It ultimately became a standard, then a commodity, since everyone copied it. But once upon a time, it was completely unique.

EM: Your business was doing well, so why sue Freeman?

JM: You have to understand the corner we were painted into. Our first show, for example, was in Atlanta for the United States Independent Telephone Association (USITA), which met three times per year around the country. We were getting maybe 10 to 15 jobs at USITA and shows like it. That sounds pretty good, but they were all 10-by-10-foot and 20-by-20-foot booths. The GCs didn't mind us having these table scraps, because the truth is these jobs had tiny profit margins. And the really good carpenters only worked on the larger projects because they could rack up the hours on those jobs. We couldn't seem to break through that invisible barrier.

Things came to a head with the 1983 OTC show in Houston. It had as many as 2,500 exhibitors and was maybe the biggest trade show in the United States in terms of square footage at that time. We were looking forward to getting some substantial work there — and then Doug Ducate, who managed OTC, declared the show would be closed to outside contractors. He said if exhibitors wanted labor, they had to get it through Freeman, end of story. We were stunned. We thought if they beat us on this, we won't have a business to go back to. If we cave now, sooner or later we'll lose everything we built, because Freeman and the show organizers working with them will see that we blinked. So we hired an attorney in Dallas and decided to file an antitrust suit to break their monopoly.

In the first week of the trial, a business agent from the labor union in Houston said under oath that he was bribed to not give us labor at the OTC show. We basically started opening the champagne right then. I mean, how could anyone rule against us after an admission like that? Then our lawyer gave us the news that we had to prove — if I remember right — seven different parts of law for an antitrust action to succeed. As juicy as the business agent's admission was, it wasn't enough.

EM: What was the outcome of the trial?

JM: After about a year, we got a deferred verdict which, boiled down, meant we couldn't satisfy all the conditions to prove an antirust charge. But in losing, we still won. Tradeshow Week — which all of the show organizers read — framed our case as an idea whose time had come, and that there was no good basis for the status quo. Show organizers should get ahead of the curve and allow companies like I&D to have an equal footing with GCs.

The show organizers started thinking that they would have to win lawsuits every time — and companies like us had to win only once. So they saw the writing on the wall, and opened up to us. And business really started to take off. There's something about the American character that loves the underdogs, and I&D was clearly the little guy in this particular fight.

EM:

EM: You broke the back of the GCs, so why did you later switch gears and start Nth Degree Inc.?

JM: All good things must come to an end, right? At that time, Intel Corp. was one of our three biggest clients. We had pitched a national contract to their reps to handle all their shows nationally.

They bought the idea, and we signed a nationwide contract with Intel that also led to us traveling to Brazil with the company for their shows there. That made us, I believe, the first EAC to do any international work, which resulted in even more international work for companies such as Compaq Computer Corp. So you can see Intel and I&D were closely entwined. Too close, as it turned out.

Years later in the mid-1990s, I was having dinner with Intel's marketing/communications director who told me we were going to lose 30 percent of their business the next year because they were going to do fewer trade shows and concentrate more on private corporate events. They wanted a company that handled badging systems, understood data management, and was proficient in booking flights and hotel rooms and arranging meals. Intel didn't think we would be able to help them with these needs. I realized then the name I&D had made our company synonymous with install and dismantle, but that advantage turned out to be a double-edged sword because that's all Intel could see us as: an I&D company.

EM: How did you recover from a potential disaster like that?

JM: I was shocked. I had never really heard of private corporate events before. I started talking about the situation with a friend I had made over the years, a former show manager named Fred O'Keefe, who, as it turned out, managed corporate events with his company, Danieli & O'Keefe Associates, in Massachusetts. The wheels started spinning. One thing led to another, and in 1996 we bought them out. Now we could do for events what I&D did for trade shows.

EM: What do you think is the legacy you leave behind?

JM: At age 69, I look back and the one thread that runs throughout my life is teaching. At I&D, we extended the idea of teaching to the whole company, especially after we had expanded into three, four, and five cities. There was a three-day-long training session, with slideshows on the company's history. But we also tried to create a culture with our teaching. We taught the structure of the exhibiting world: the industry sectors, the unions, the associations, the organizers. It provided them a thorough grounding no one else offered.

On the third day, we taught something we visually depicted as a triangle. The left side of the triangle represented the importance of doing things in detail and fulfilling your promises. On the right was a sense of urgency, because when you attack even the smallest tasks for a client with urgency, you make them feel valued. Connecting the two sides was the base, that of overcoming any obstacles you face for a client. In the triangle's interior was the net result of doing all these things well: trust. If you gained a reputation for trustworthiness, you gained influence and intimacy.

EM: As you look back, is there anything that you would do differently?

JM: Not one thing. I say that equally about my professional and my personal life. I've had many hard times, but my life has been full. Along the way I have been fortunate to have had some excellent mentors who always seemed to arrive at the right time. And I hope I have become an equally good mentor to others when they needed one.